In this dangerous historical moment, we need to urgently heed Plato’s warning and re-imagine our social institutions so that they can better contain sources of toxicity and instead empower progressive change if impending catastrophes are to be faced and avoided. Such re-imagining is particularly pressing for the social institution of democracy.

“I think the writing is on the wall for democracy and it has been for at least a decade. The symptoms we know well: the hollowing out of political parties; rising disaffection of citizens against politicians, parties, politics; the growing gap between rich and poor – practically every democracy has seen a 40-year widening of the gap, and that’s a violation of the ethic of equality, which is essential to democracy; the penetration of politics by dark money; the growing ruination of biomes in which democracies operate.”

Australia is lucky – we have one of the strongest and most effective democracies in the world. However, our democratic institutions were developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and were designed for a different time. As with all areas of life democracies need to adapt and change as the world changes…. and times are changing fast.

Social and technological changes are making it increasingly difficult for our democratic institutions to operate effectively. Democracies worldwide face significant risks because of diminished trust in politicians, governments, and institutions, a general disillusionment with government and an increasingly polarised community.

These issues are being driven in part by echo chambers, spaces that only expose us to views that reinforce our existing beliefs and perspectives. The consequence of this is that we no longer have ‘shared stories’ that shape our civilisation; instead, we exist in silos only hearing, or perhaps trusting, those in our tribe.

Rising inequality in many democracies is also playing a significant role, as is the rise of populism.

The impact? Substantial reform by governments is becoming very difficult at a time when we are needing to make ever complex and difficult economic, social and environmental trade-offs. Our democratic systems need refinement to enable them to continue to operate effectively. We would argue that a range of reforms (or perhaps tweaks!) are needed to our democratic systems. Giving citizens a way into the political process through large scale participative methods offers one way forward to address a number of the challenges.

“Democracies around the world are under stress. In this moment, it is critical to work on the challenges to democracy”

“There is growing disillusionment with politicians and, by extension, with the political system, in Australia. There is diminishing respect for the rule of law, political corruption, poor standards of personal behaviour and failure of leadership have affected people’s confidence in the system of government”.

“Fewer Australians think about and talk about politics, which is a bad sign. There’s a real stalemate in terms of voters being angry, parties not caring and no one really knowing what to do. It’s not sustainable indefinitely”.

The 2019 Guardian Essential poll found that:

The Australian Election Survey found in 2016 that disillusionment had reached a threshold where Australia was beginning to see corrosive popular disaffection with the political class

“This loss of trust threatens the social license to operate for Australia’s institutions, restricting their ability to enact long-term strategies. Unless trust can be restored, Australia will find it difficult to build consensus on the long-term solutions required to address the other challenges.”

Trust is the foundation upon which the legitimacy of public institutions is built and is crucial for maintaining social cohesion. Trust is important for the success of a wide range of public policies that depend on behavioural responses from the public. For example, public trust leads to greater compliance with regulations and the tax system. Trust is necessary to increase the confidence of the public as well as business.

A strong trusting relationship also provides governments with a considerable buffer to their ‘social licence to operate’. Where governments are trusted, the community is much more likely to accept politically challenging or difficult decisions – as the public have faith that the government is acting in their best interests.

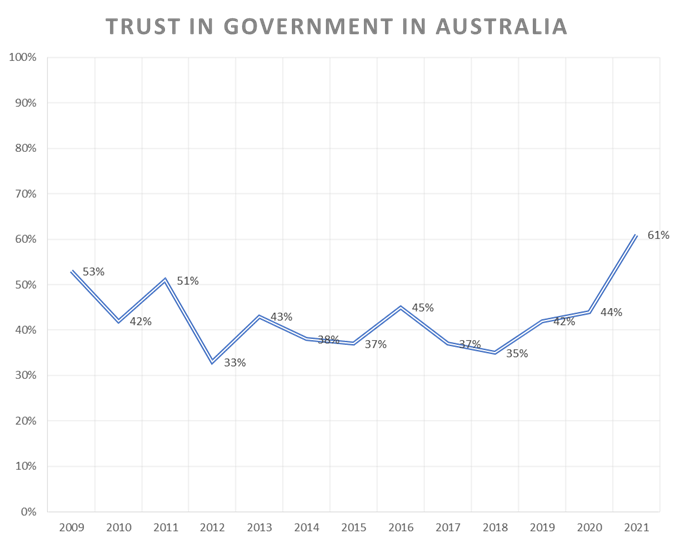

The trend in levels of trust had been downward for the last 20 years until COVID hit.

After each federal election, a study is undertaken by the Australian National University analysing the outcome at that last election. It is known as the Australian Electoral Study. It is interesting to note that the Australian Electoral Study in 2019 found that trust in government had reached its lowest level on record, with data covering a 50-year period since 1969. Trust in government had declined by nearly 20% between 2007 and 2019. In addition, it found that 56% of Australians believe that the government is run for ‘a few big interests’, while just 12% believe the government is run for ‘all the people.

The data in the Table above was taken from the Edelman Survey, which is an international study looking at trust in business, government, media and NGO’s. Time will tell whether the results for 2021 is an anomaly, however given that the conditions for trust to build are being undermined by the echo chamber (amongst other things), we are expecting for trust levels to return to the previous downward trajectory over the coming couple of years.

“One of the key drivers of democratic decay in new and established democracies is intense polarization, where political opponents begin to regard each other as existential enemies, allowing incumbents to justify abuses of democratic norms to restrain the opposition, and encouraging the opposition to use “any means necessary” to (re)gain power.”

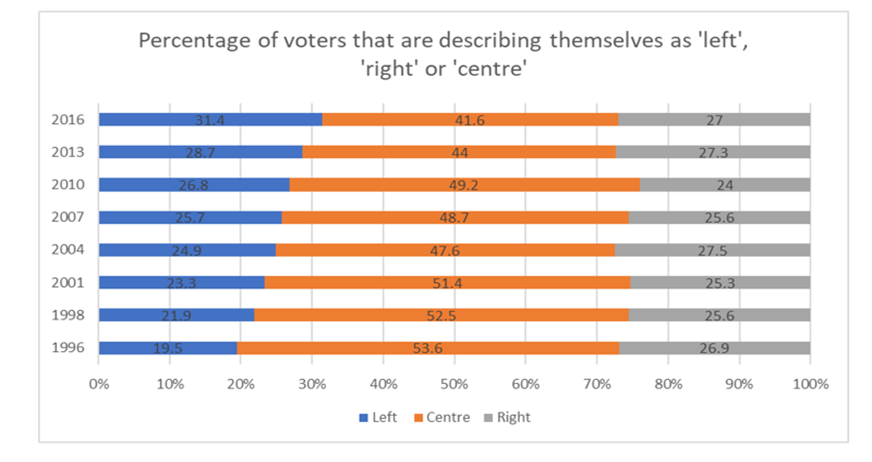

In Australia we saw increased political polarisation between 1996 and 2016. This can be seen by the results of the Australian Electoral Study over this period presented in the table below. Unfortunately, the Australian Electoral Study did not ask this question in their 2019 survey. The 2019 study did however find increasing divisions between:

We can also see the polarisation happening in our communities – polarised debate on talk back radio, polarised debate in online forums, the polarised debate through our media outlets and even the increasing polarised debate and positioning by our politicians in response to the community.

“Online communities are fragmenting into warring tribes with common ground and reasonable compromise falling victim to the culture wars pitting “us” against “them”. Moreover, the dangers posed by big-tech platforms and their use and management of citizens’ data has fuelled the climate of polarisation and undermined social cohesion.”

We have a significant problem with how we are analysing the information we receive. While we are receiving more information than ever before, instead of making us more likely to agree with each other, “informational diversity” has instead taken us further away from an agreed upon truth and made us more likely to disagree.

Up until recently, the echo chamber effect was thought to be as a consequence of us not reading the views of others. Recently, research has clarified that echo chambers aren’t necessarily about not seeing or reading information from those with ideological differences, but more about discounting or discrediting them based on their contradiction to our own worldviews.

Research out of the United States has demonstrated that as with online echo chambers, news media consumers do view sources across the political divide, but rates of mistrust of those sources are high, with 77% of liberals mistrusting Fox News and 67% of conservatives distrusting CNN. Echo chambers aren’t being created because users or readers are blind to other information (or not receiving it) but because they discredit alternative views and use their trusted sources to reinforce their own world view. “Ultimately then, two people can hold opposite accounts of reality because that’s the reality they perceive within their respective echo chambers. And therein lies the danger—although one account may be more objectively accurate than another, echo chambers transform false perception into subjective reality just the same.”

These online echo chambers represent a kind of “confirmation bias on steroids” driven not only by filter bubbles built into search engines and social media sites, but also by active “challenge avoidance” (i.e. not wanting to find out that we’re wrong) and “reinforcement seeking” (wanting to find out that we’re right) by readers.This feeds and reinforces our desire to access our information online as these new media use algorithms to deliver information directly to a user’s personal account that accords with our own existing bias.

Recent work on how to counteract opinion polarization on social networks has also appeared, and initial results suggest that facilitating interaction among chosen individuals in polarized communities can alleviate the issue.

“Social learning improves decision making only when individuals each have different information. When the information from outside sources (such as magazines, TV, and radio) became too similar, we observed, social trading became reliably unprofitable. In such circumstances, not only does groupthink not pay, but betting against groupthink becomes a great trading strategy.”

It is argued that high levels of inequality will continue to undermine democracy. Apart from the fact that inequality is contrary to the concept of democratic principles, inequality also creates challenges for the effective operation of a democracy. For example, there is considerable research linking inequality with polarisation in the United States and Europe.

Research in Europe has found that increasing inequality leads on average to more support for left-wing parties and more support for far-right parties among older individuals. In the US, researchers have found that “states showing greater degrees of political polarization are associated with higher levels of income inequality. In particular, a 1 percent rise in the 90-10 earnings gap is associated with a 0.18 percentage point increase in political polarization – that is, the share of individuals identifying as extreme liberals minus those reporting as extreme conservatives goes up by that amount. For the 90-50 earnings gap, it’s 0.22 percentage point.”

It is less clear to what extent inequality is contributing to polarisation in Australia. We have not been able to find research into the connection between, inequality and polarisation in Australia, but one could assume that like the US and Europe, it does play a role.

Various data sources show income and wealth inequality exists in Australia, but there is less agreement among analysts about whether inequality is worsening, improving or staying at around the same level over time.

ACOSS provide data indicating that people in the highest 20% of the wealth scale hold nearly two thirds of all wealth (64%), while those in the lowest 60% hold less than a fifth of wealth (17%). The average wealth of a household in the highest 20% wealth group, at $3.25 million, is six times that of the middle 20% wealth group, at $565,000, and over ninety times that of the lowest 20% wealth group, at $36,000. The average wealth of the highest 5% wealth group is $6,795,000.

ACOSS state that inequality “was no higher in 2020 than in 2007-08, however it was still higher than in any year between 1999-00 and 2007-08, and almost certainly than in any year between 1980 and 1999”.

“Given the dangerous erosion of democracy in many places, a more holistic model of democracy is required which involves a combination of deliberative, participatory, direct and representative forms of democracy, where each may act to overcome the deficiencies of the other. Within this ‘vibrant democratic ecology’ there is an urgent need for participatory and deliberative democratic innovations that empower wider and deeper forms of citizen participation.”

In this paper we identify a range of interconnected problems which together are contributing to challenges to the effective operation of our democracy. There are of course a vast range of solutions to these issues from regulating search engines and social media to reduce the impact of the echo chamber, publicly funded political campaigns or caps on political donations to build trust in institutions, parliamentary processes to encourage collaboration, and addressing inequality. Just to name a few.

There is no silver bullet.

Various reforms to address different aspects will be important, however at democracyCo our focus is on one method – increasing participation in the work of government. We are focused on this area because our experience and research tells us that it helps – that using an area of participative engagement known as deliberative democracy in particular helps to address polarisation, builds trust among participants and builds empathy in our communities.

We are also focused on this space because, improving participation in the work of government can be achieved without constitutional reform, without legislation, without even decisions of Cabinet. This is an area in which the public service can act, individual local members can act, and individual Ministers can act. Even the private sector can act. As a consequence, we believe that increasing participation of the community in the decisions of government is ‘low hanging fruit’ in terms of democratic reform …

In addition, apart from these broader benefits to democracy, improving the quality of participative methods will bring the following benefits to your work in policy making, project management and service development:

“The biggest constraint on the power of a ruling politician right now is that the public don’t trust them. Deliberation will give politicians more power, because real power relies on having citizens on board”.

The OECD has reflected on the importance of civic participation in democracies to addressing issues of trust.

They state:

“Participation and institutional trust are positively related. Civic-minded citizens are more participative and have higher levels of trust than passive citizens. Additionally, trust in public institutions is positively correlated with government “openness”, which can be interpreted as “providing an explanation of government’s actions. People’s belief that they have a say in what government does (described as external political efficacy), and that they can participate and understand politics (described as internal political efficacy) are positively correlated with engagement and participation. Besides, high levels of political efficacy are considered desirable for the stability of democracies, as they are linked to people’s feeling that they have power to influence governments’ actions”.

This is reinforced by recent research out of Singapore into their first three citizen juries which found that the processes-built trust between government and participants.

Research from the United States also highlights that using participative methods of engagement – particularly deliberative methods of engagement help to address polarisation, improve empathy and enable groups with diverse views to come to agreement with each other about the way best way forward. A recent study by Stanford University highlighted these benefits. Refer to the below text box for an overview. Similar results were found through some research in Vancouver in 2017. In this example researchers asked 1,500 participants to talk about polarising issues relating to AI. Each participant was asked to judge whether it was ethically wrong or right on their own before they were broken up into groups of three people, where they were asked to reach consensus with each other. Each group was asked to discuss the issues for two minutes and unanimously come up with a single number that expressed the correctness of that action on the same o-to-10 scale. One-third of the groups that began with participants holding completely opposite views on highly polarized issues were able to reach a consensus.

There is no silver bullet.

Various reforms to address different aspects will be important, however at democracyCo our focus is on one method – increasing participation in the work of government. We are focused on this area because our experience and research tells us that it helps – that using an area of participative engagement known as deliberative democracy in particular helps to address polarisation, builds trust among participants and builds empathy in our communities.

We are also focused on this space because, improving participation in the work of government can be achieved without constitutional reform, without legislation, without even decisions of Cabinet. This is an area in which the public service can act, individual local members can act, and individual Ministers can act. Even the private sector can act. As a consequence, we believe that increasing participation of the community in the decisions of government is ‘low hanging fruit’ in terms of democratic reform …

In addition, apart from these broader benefits to democracy, improving the quality of participative methods will bring the following benefits to your work in policy making, project management and service development:

Before COVID-19 pandemic hit the US, over 500 American voters, from across the country met to discuss the most pressing issues of the 2020 election: immigration, health care, the economy, the environment and foreign policy.

Before participants started, they rated their support (or opposition) for 49 policy proposals. The researchers found extreme partisan-based polarization between Democrats and Republicans on 26 of the proposals. But after a weekend of deliberation, the two parties moved closer on 22 out of the 26 proposals and in 19 of those, movements were significant.

One of the most polarizing topics – deportation of undocumented immigrants. Before deliberation – 79 percent of Republicans supported the proposal “undocumented immigrants should be forced to return to their home countries before applying to legally come back to the U.S. to live and work permanently.” After -the number was halved: 40 percent in support.

Research lead James Fishkin reflected on the change he saw in participants – “People began to see one another as human beings. They got to know one another, and they began to develop something that is so rare in our hyper-polarized society: empathy.”

The researchers also found that people came to like each other more. After deliberation, dislike between the two parties diminished: Democrats’ “feeling thermometer” ratings of Republicans rose 13 points with deliberation. Republicans’ ratings of Democrats went up 14 points.

Could deliberative democracy depolarize America? | Stanford News

“If you have a moderated discussion with diverse others, you open up to people from different socio-demographic backgrounds and different points of view, you learn to listen to them as well as speak to them. If the discussions are in-depth enough, people will depolarize.”

There is no doubt that democracies around the world face considerable challenges, in substantial part driven by changes to how we receive our information, and they will face increasing pressure over time as the complexity of decisions get harder and more urgent within a resource constrained world.

We are at a key point in history. We have an opportunity to make the changes needed to our democracy to make them as resilient as possible for the future. Some of these changes are harder than others.

One simple thing that can be done is to change how we involve citizens in the processes of government and public policy development and make sure that we are involving them in ways that build trust, respect and empathy – not only between public servants, decision makers and citizens but between the citizens themselves. Participative forms of engagement such as deliberative democracy provide us with the opportunity to build bridges and find solutions to complex public policy questions that the vast majority can live with. Utilising such engagement tools will not only contribute to an improved democratic environment but also assist decision makers in achieving sustainable reform.

For a fully referenced version of this paper, download the PDF here

If you want to learn more about how we can help you, we’d love to hear from you. Simply send us an email and we’ll be touch soon.

DemocracyCo’s work is undertaken on the lands and waters of Australia’s First Nations people. As we collaborate together, democracyCo looks to our First Nations people, the worlds oldest living culture, for guidance that will help sustain our connection to Country and inform the work that we do to bring people together. Our work is in service to Reconciliation and to moving forward together.

Privacy Policy • © 2024 democracyCo – All rights reserved • Website by Seventysix Creative